Technical Report

NeighborFinder_technical_report.Rmd

library(rmarkdown)

library(knitr)

library(neighborfinder)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'neighborfinder'

#> The following object is masked from 'package:rmarkdown':

#>

#> metadataWhy use NeighborFinder?

NeighborFinder helps you find the direct neighbors of a certain object of interest (bacterial species, functional module, etc).

Applying NeighborFinder to multiple datasets makes predictions more robust. Identified neighbors can thus be used to design microbial communities, probiotics or live biotherapeutic products (LBP).

NeighborFinder can also help to identify specific ecological niches linked to particular diseases.

Input dataframe format

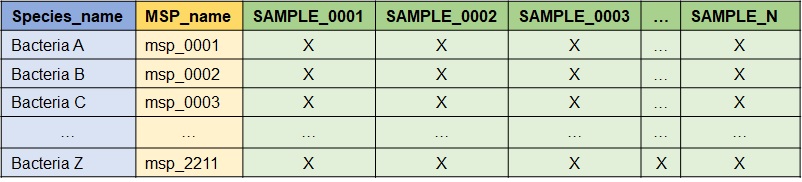

The required data format in input is as follows: module IDs are the rows and samples are the columns. The first column must be the modules name (e.g. species), the second is the module ID (e.g. msp), and each subsequent column is a sample. “X” is a numeric value corresponding to an abundance provided either as count or a metagenomic abundance. Here is an example when the modules name is the species name and the module ID is the MSP_name.

What is behind apply_NeighborFinder() ?

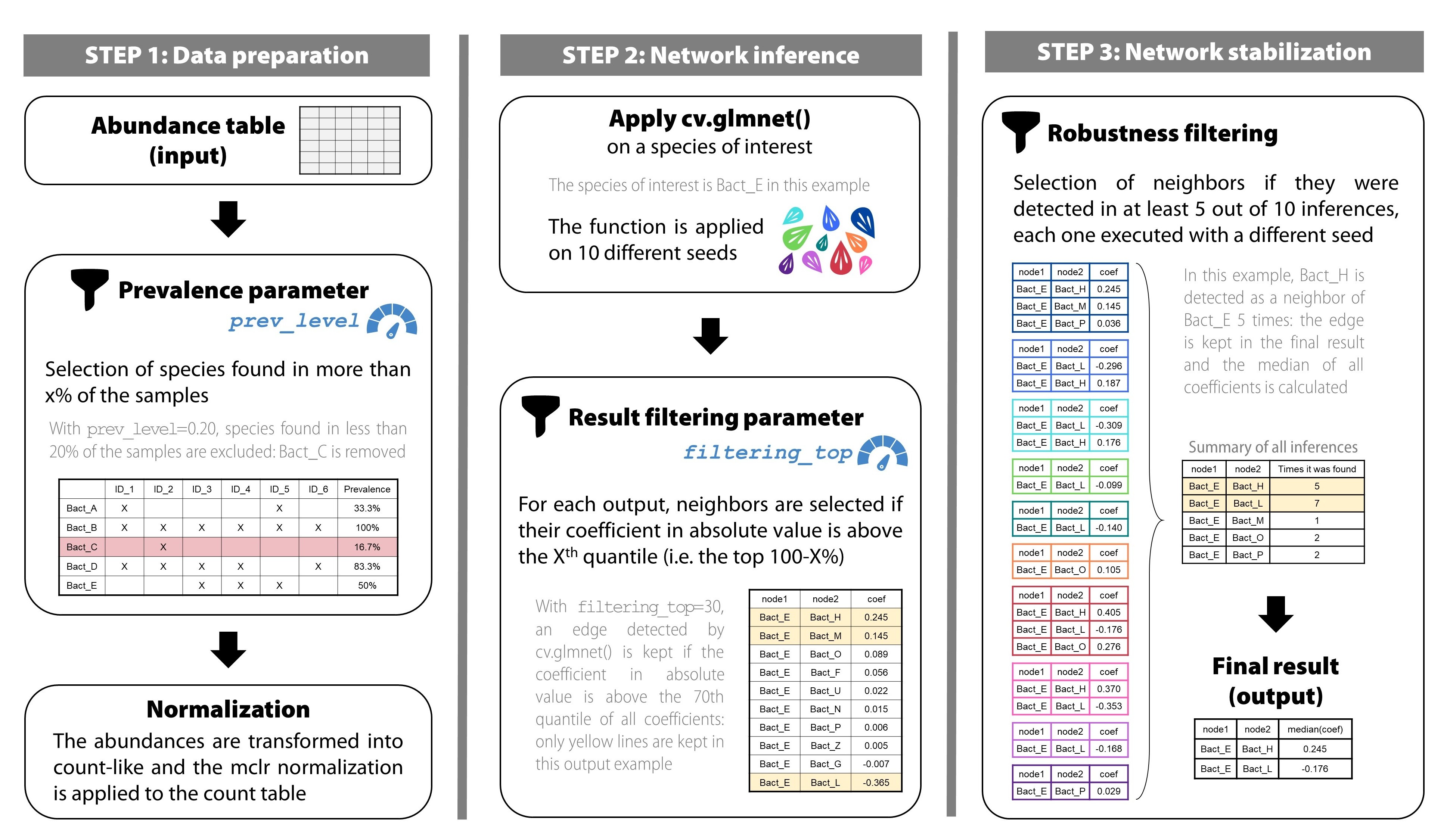

Here is a description of how the function works.

1) Pre-processing: Counts & Normalization

a) Prevalence filter & shotgun pre-treatment

The first step of apply_NeighborFinder() is to filter

the input abundance data, provided in the above format, using the

parameter prev_level. This step helps simplify the dataset

by filtering out rare species.

The transformation of the abundance data into a count table consists

in first transposing the data (so that the samples are in rows and the

module IDs are in columns). Then, the abundances are transformed to

counts using get_count_table() extracted from the

OneNet package. This is done by dividing all values by the

smallest positive abundance and rounding the results, so that the

minimum count is 1.

where where is the abundance table and the resulting count table. Note that the rows of (and ) are samples and the columns are module IDs .

b) Normalization

The next step consists in applying a mclr normalization to the previously transformed abundance data. Here is the equation corresponding to the mclr transformation:

where is the count table and the resulting normalized count table. Unlike the clr normalization, mclr preserves the zeros in the dataset.

The function is defined as follows. Consider a vector of compositions, and and without loss of generality, assume that the first elements of are zero, and that all other elements are positive.

Then is defined by:

where is the geometric mean of the non-zero elements of .

When is applied to the abundance table , we apply it rowwise (that is to each sample ) and use

where .

2) Regularized linear regressions

a) Simple case: no covariates

We consider a linear regression problem where we regress the

abundance

of module

against the abundances of all others modules

.

The function glmnet::cv.glmnet() is applied on the

normalized data 10 times, each time with a different seed. The following

model is used:

where is the normalized count table obtained at the end of step 1) and designates the column of the module of interest in . is the regression coefficient of against , and is the residual error, assumed to be gaussian with covariance.

Since is usually bigger than and we want a sparse vector , we use –regularization to select a small number of non null coefficients in . The modules for which corresponds to a potential neighbors of module .

This translates to the following minimization problem:

where

is the design matrix composed of the abundances of all modules but

,

and

is the penalization term enforcing the strength of the regularization

and thus the number of non null coefficients. We solve this problem

using glmnet::glasso() and use cross-validation to tune the

parameter

.

b) Handling covariates

Covariates can be included in the model by considering an made of two distinct components: , previously defined, and , the design matrix of the covariates.

the metadata matrix where some columns are considered as covariates. Here is the necessary transformation:

$[\matrix{D&C_{-j0}}]$ $[\matrix{\alpha\\\theta}]$

The penalization only applies on coefficients and not on .

Minimization of the objective function:

In practice,

and

are concatenated into a single matrix which is used as the input of

cv.glmnet() and

is constructed from a covariate dataframe using either (i) the

formula interface, or (ii) specifying the name of a single

column used as covariate.

To use covariates, 3 additional arguments are required:

covar: takes a formula or the name of the column of the covariate in the metadata table.meta_df: the dataframe giving metadata information.sample_col: the name of the column in metadata indicating the sample names.

See part “Apply NeighborFinder with covariate option” in the vignette for a detailed example.

3) Post-processing

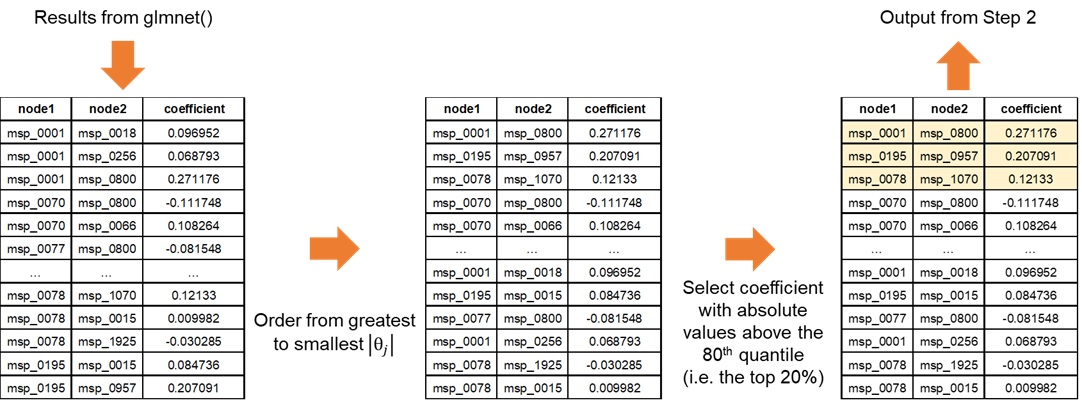

a) Filtering the results

This step enables NeighborFinder to have better performances than

with the naive glmnet method. For each seed-generated result, a filter

is applied to increase the reliability of detected interactions. This is

done with the top_filtering parameter: it consists in

keeping only the strongest coefficients. If top_filtering

is set to 10%, the coefficients conserved must be greater in absolute

value than the 90th quantile of all coefficients detected for the

neighbors of a species of interest.

b) Increasing robusteness

To gain in robustness, only neighbors detected several times are

kept. The function apply_NF_simple() is run on 10 seeds and

results found are kept if only found in at least half of the seeds. This

process ensures more robust results. This step merges the 10 filtered

results (each corresponding to a seed) and eliminates edges detected in

less than half of the results. For a kept interaction, the median of the

different coefficients is calculated and saved in the final output. The

final result is an edge table of the interactions that were stronger and

found in at least half of the 10 seed-generated results.

Performance scores were way better with this repetition approach than running the developed method on a single seed (see Figure 4).

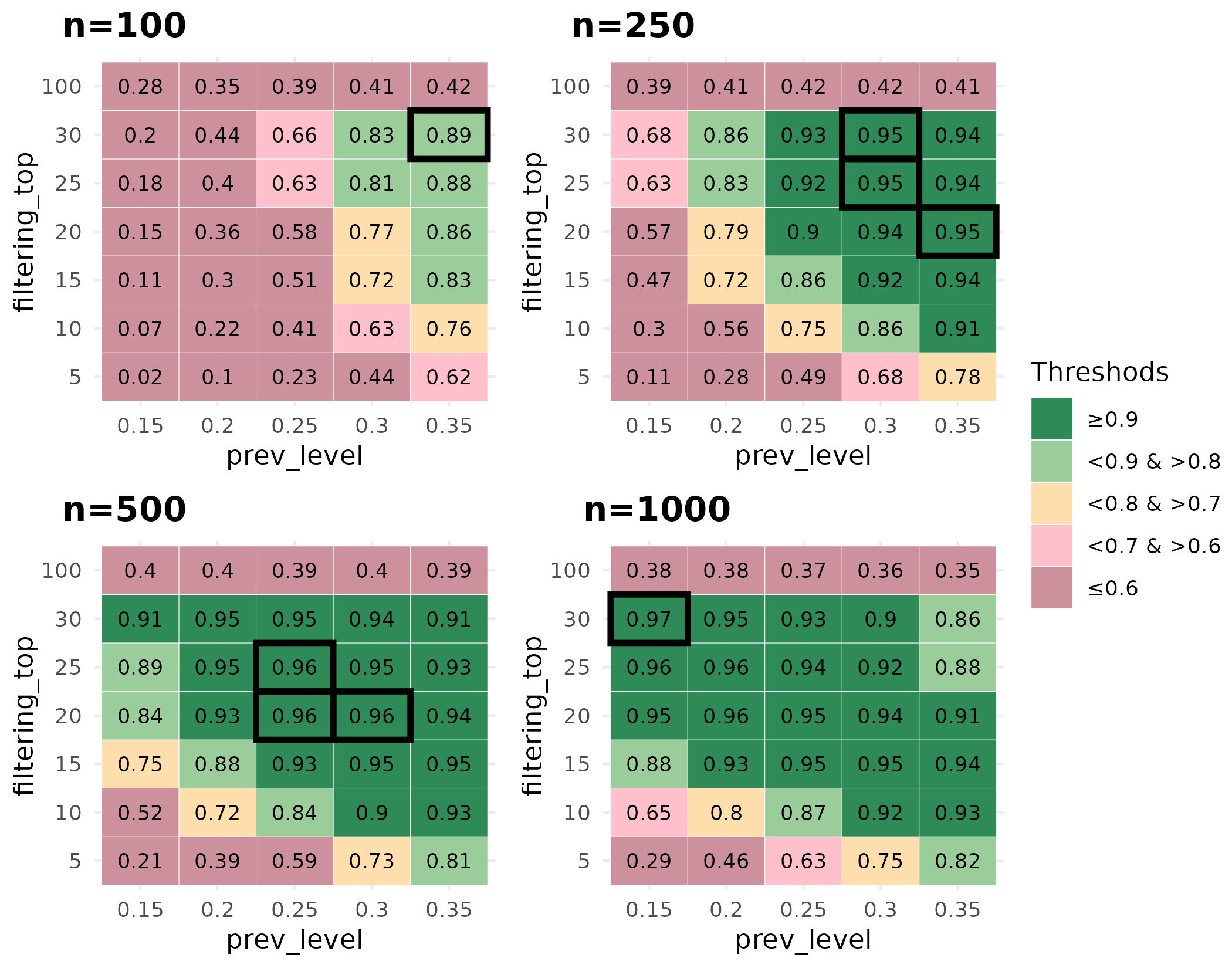

How to calibrate the parameters values ?

The function apply_neighborfinder() has two important

parameters (prev_level and top_filtering) that

shape the output. It is also acknowledged that the dataset size usually

has an impact on the generated network. Our performance assessment

strategy therefore consisted in covering a range of values for both

parameters, with the aim of providing users with guidelines to pick the

most suitable combination for their dataset size. We tested the

performance of NeighborFinder on eight shotgun metagenomic cohorts

(sample sizes ranging from 347 to 1084) detailed here

doi_recherhche_data_gouv.

For each of the eight large cohorts, a graph with “cluster-like”

structure was generated with the graph_step() function. A

precision matrix

with non-null coefficients respecting the graph topology was produced

and then inverted to produce a covariance matrix

.

Semi-synthetic simulated datasets of sizes n=100, n=250, n=500, and

n=1000 samples were generated using gaussian copula from the covariance

matrix

and the original count matrix to produce count tables that (i)

have the same marginal counts distributions as the original cohort

(ii) while enforcing the correlation between taxa encoded in

.

The graph edges are here considered as true edges (ground truth).

On 10 different seeds, for each value of prev_level

tested (from 15% to 35%, by increment of 5%), and for each bacterial

species, the cv.glmnet() function was applied to each

simulated dataset (via the function

cvglm_to_coeffs_by_object() from the

NeighborFinder package). This part corresponds to the first

steps of the method (see Figure 2, step 1 and step 2 at top). The

results were then filtered as in the procedure of

apply_NeighborFinder() (see Figure 2, step 2 at bottom) to

keep only a filtering_top percentage of the coefficients,

ranging from 5% to 30% in 5% increments, and 100% corresponding to not

filtering results. The final results were obtained by going through the

last step of the method (see Figure 2 step 3) with the selection of

interactions if they were detected in at least 5 of the 10 results (each

corresponding to a seed) for each pre-mentioned case.

Performance scores (F1) were calculated by comparing the true edges

of the graph with the detected neighbors, averaging on bacterial species

and cohort datasets. The same procedure was done on simulated datasets

of size n=50, but with a prev_level range from 30% to 60%

by increment of 5%.

Based on the performance scores calculated on simulated data,

parameter pair choices (prev_level and

filtering_top) should be adjusted according to the size of

the dataset on which the user wishes to use NeighborFinder. When dealing

with large datasets, the user has plenty of parameter combinations that

lead to an equivalent expected performance, with the dark green areas

indicating a high F1 score (>=0.9) in Figure 4. One choice could be

to select a low value of prev_filter to include as many

bacterial species as possible and then choose the

filtering_top value to ensure satisfactory optimum

performance. For example: with n=1000, prev_level=0.15 and

filtering_top=30. As the dataset size decreases, the user

is advised to increase the prev_level value while

maintaining a high value of filtering_top.

The function choose_params_values() has been designed to

allow the user to obtain a more specific indication based on the dataset

provided and the module of interest. This function works in the same way

as the procedure described previously:

Generation of a graph

Simulation of a dataset respecting the dependencies between taxa encoded in the graph, for different prevalence levels

Application of

apply_NF_simple()on 10 seeds, with and without filtering top results (testing different percentages)Application of the robustness step (filtering interactions if they are found in at least half of the seeds-generated results)

Comparison and computation of F1 score:

before (

filtering_top=100 and no robustness step)after the filtering & robustness steps

The user can then decide which values of these parameters to use for

downstream analysis and pass them on to

apply_NeighborFinder() using the arguments

prev_level and filtering_top.